Opening lines: "Check this out. This dude named Andres Dahl holds the world record for blowing up the most balloons...with his nose. Yeah. That's true. Not sure how he found out that was some special talent, and I can't even imagine how much snot must be in those balloons, but hey, it's a thing and Andrew's the best at it."

Castle Crenshaw's voice sounds upbeat and sarcastic, but a couple of pages after the opening lines above, we find out that one night years ago, Castle's dad had been drinking and when Castle's mom fought back against the usual physical abuse, Castle's dad grabbed a pistol Castle and his mom ran for it, and Castle's dad got arrested and taken to jail. The story, however, takes place years later and opens as Castle stands looking through a chain link fence at tryouts for an all-city track team. On a whim, he walks over and challenges one of the kids to a race. Though the coach is angry about the interruption, he gives Castle one chance. When Castle ties the kid, the coach convinces Castle to give the team a try, though Castle isn't very enthusiastic about it.

And of course, it doesn't go smoothly. Castle, who takes on the nickname Ghost, is fast but insecure, can be a hard worker, but is inconsistent, and is embarassed by his tennis shoes so he shoplifts a better pair. He is nearly kicked off the team several times, and yet it is clear to the reader that Ghost has found a home.

One of the things I love most about this book was Coach Brody. He is a tough guy who cares about the kids on his team and is willing to push, encourage, cajole, and challenge them to get them to commit to something and experience what being excellent at something can do for them. Ghost finds out that, though Coach Brody drives a cab to pay the rent, he is a former Olympic team member. Ghost also finds out that his fellow team members, who he initially doesn't think much of, have their own stories and eventually become people he cares for.

My daughter is a runner and loved this book. I am not a runner and I loved this book. I would be best for maybe fourth grade at least through middle school (my daughter read it last year, when she was an eighth grader). There is nothing in here that I could imagine would be challenged, unless someone objects to the authentic depiction of poverty and injustice and the ability for kids who have been through a lot to still be able to challenge themselves..

If you teach English Language Arts (or Phys Ed, for that matter) , you need this for your classroom library. Seriously. You might also think about using it for literature circles or incorporating it in a unit.

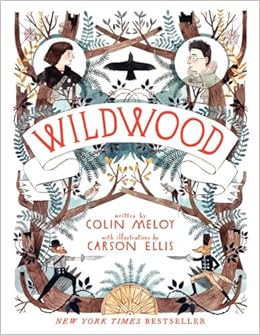

Meloy, Colin; Ellis, Carson (2011) Wildwood. New York: Harpercollins.

Opening line: "How five crows managed to lift a twenty-pound baby boy into the air was beyond Prue, but that was certainly the least of her worries."

I have always loved books that take me to other worlds. Narnia, Middle Earth, Xanth, Barsoom, and other worlds fascinated me when I was younger. J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series introduced the idea of another world that coexisted in the same space as ours. Eoin Colfer's Artemis Fowl series extended that idea. Now along comes Colin Meloy (Lead singer and songwriter of the band The Decemberists) who introduces us to the Wildwood. The Wildwood is just outside of St. Johns, a neighborhood of Portland, Oregon. Usually the Wildwood stays separate from our world, with people coincidentally choosing never to go there and thinking nothing of it, but some people are able to penetrate the barrier.

Prue and her classmate Curtis, chasing a murder of crows who have abducted Prue's baby brother Mac, find themselves in the Wildwood, a land of coyote soldiers, human bureaucrats, owl kings, and many other animal factions which seem to have trouble working together. Prue escapes the evil Dowager Empress and finds her way out of the Wildwood, but she also learns something about her parents and her past. She decides to return to the Wildwood, even though that idea of doing so scares her.

Prue and Curtis find themselves desperately fighting to stop the Dowager Empress before she sacrifices Mac, reawakens the Magical Ivy, and destroys the Wildwood (and maybe the whole world). But to do that they will have to unite the bandits, the mystics, and the bird kingdom.

This is a world you can immerse yourself in. The protagonists are likable and bad guys fun to dislike. Other than the fact it is fantasy, there is nothing here I could imagine anyone objecting to. This novel would work well for fifth grade and up, though the fact that this first volume in the series weighs in at over 540 pages may give less experienced readers pause (and delight the readers you cannot recommend books to fast enough). This would be good for your classroom library.

Lu, Marie ((2011) Legend New York: Penguin.

Opening lines: "My mother thinks I am dead. Obviously I'm not dead, but it's safer for her to think so. At least once a month I see my wanted poster flashed on the JumboTrons scattered throughout Downtown Los Angeles."

Day cannot be captured. He strikes against the California Republic, destroying military weapons, stealing money, and always escaping before anyone even sees him. Also, he never kills. Then when an attempt to steal medicine for his family goes wrong, he throws a knife at a soldier, who later dies. That soldier's sister, June Iparis, the only person to ever get a perfect score in her trials (sort of comprehensive standardized tests), is assigned to find him.

This dystopian novel includes themes of deception versus truth, power inequity, and loyalty to family versus the state,. It also explores some interesting ideas of bioethics. Told in alternating voices of Day and June, it is primarily an adventure book, but, like many of the better dystopian novels, digs into some serious ideas worth discussing.

This book would work best for high school, both in your classroom library, but also potentially as part of a dystopian literature unit. There is nothing here particularly objectionable beyond some non-extreme violence and romance.

Conoghan, Brian (2016) The Bombs that Brought Us Together. New York: Bloomsbury.

Opening lines: "It was hard to remain silent. I tried. I really did, but my breathing kept getting louder as I gasped for clean air. My body was trembling, adding noise to the silence."

Charlie Law is fourteen years old and lives in Little Town. His new friend, Pavel, is a refugee from Old Country. Little Town is under threat from Old Country that wants to take it over. When Old Country invades Little Town, Charlie finds himself in need of food for his family and medicine for his asthmatic mom. He ends up beholden to the Big Man, the head of a black market criminal enterprise. Charlie must make a series of decisions which have difficult consequences, and he really has little choice in how he makes those decisions. Life as a refugee in a bombed out city ruled by an egomaniacal thug is not fun. Neither is this book (but of course, it isn't trying to be).

This would seem at first glance like a good choice for teachers who might want to help their students explore the plight of refugees. Honestly,though, it has some significant flaws. Though Charlie and Pav refer to themselves as friends, I didn't see much evidence of any real friendship there. After wading through a lot of darkness, violence, vulgarity, tension, and despair, we get to see justice (sort of), friendship (somewhat), and the beginnings of a romance between Charlie and Erin F. (someday), win out.

And there is a part of me that really believes that high school students should not just be reading happily-ever-after books, but I worry that it would be hard for students to identify or even care for Charlie. I also wonder if many of them would be interested in it.

Although Charlie himself is between middle school and high school, I see this more as a high school book. I am not sure why I think that, though. Middle school students could handle the vocabulary. There is some vulgarity in the book though it tends to be kind of obscure slangy references to pubic hair or terms like "butthole". I am not sure I would fight for this one, though.

This one would be okay for your classroom library, but I don't think it is something that you absolutely must get a hold of.

Clark, Kristin Elizabeth. (2016) Jess, Chunk, and the Road Trip to Infinity. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

Opening line: "Something about my mom's new age music makes me want to stab myself in the eye."

Within the last couple of years, it seems like the Young Adult Literature market has been flooded with books dealing with aspects of LGBTQ life. Like all other topics for books, some of these are quite good. Many of them are not as worthwhile as others. This one well worth the read.

Jess is going on a road trip from her mother's house in California to Chicago where her dad is getting married. Since the last time she saw her dad, she was a boy named Jeremy, Jess is worried about this trip so she is bringing along Chunk. Chunk was her best friend when she was a guy, and he seems to accepted her change without much fanfare. As they head west, though, Jess's increased anxiety about how people perceive her, causes her to think that everything is about her. When Chunk takes a detour to meet Annabelle, a girl he met through a Star Trek chat room, Jess is irritated by Chunks lack of attention to Jess.

While the story is told through Jess's voice, the message comes through loud and clear. Jess thinks the story is about her bravery in revealing her transformation to her father. This is what I expected, a book about Jess finding herself and discovering the courage she needs to make a successful transition and Chunk and Annabelle accepting it as well. It is actually about her eventual realization that the world doesn't revolve around her. That sets this one apart from others I have read.

This would be ideal for high school readers. While there is no graphic sex or anything like that in the book, expect it to be challenged as it does feature a romance involving a trans person (though only at the very end).

.jpg)