Opening lines: "Could you tell me a story?" asked Cole.

"It's awfully late." It was long past dark and time to be asleep. "What kind of story?"

"You know, a true story. One about a bear." We cuddled up close.

"I'll do my best," I said.

And with that, we fall into two separate stories. The first is about a veterinarian named Harry Colebourne who lives in Winnepeg. Harry is called up to fight for Canada in the First World War. While riding a troop train to a training base, Harry gets off at a station and encounters a trapper who has a bear cub with him. Harry buys the bear and takes it with him to a staging base in England. The bear, named Winnepeg, or Winnie for short, serves as a mascot for his unit. When it becomes clear that his unit will be shipped to fight on the continent, Harry drives in to London and donates his bear to the London Zoo and tearfully says goodbye. As the book puts it, that is where one story ends and another begins. Some years later, a young schoolboy named Christopher Robin Milne becomes quite taken by the bear and loves visiting him in the zoo. That bear becomes part of the basis for the beloved children's book character Winnie the Pooh.

There are a couple of things that make this book stand out as a picture book (and explain why it was honored by a Caldecott Medal). First of all, the images, which straddle the line between realism and cartoon, give us a remarkably clear sense of the bond between the bear and the soldiers. A section in the back of the book contains annotated black and white photographs from that period so that children can see images of the bear and the soldiers (and the bear with Christopher Robin) and the similarity between those photographs and some of the images in the book connect the story even more deeply with history.

Secondly, by telling two separate stories, the book does an amazing job of helping young children get the sense of how history can link together more than one generation (particularly when one picture in the back reveals that the author of the book is Harry's great-granddaughter.) For kindergarteners and first graders beginning to learn history, the book provides this veracity and the sense that old photos and documents contain fascinating narratives -- and that there is more to the stories of those who go to war than just fighting.

The book would be ideal for first grade and second, but could also be useful for introducing concepts of historical research and analysis to middle grades and high school kids.

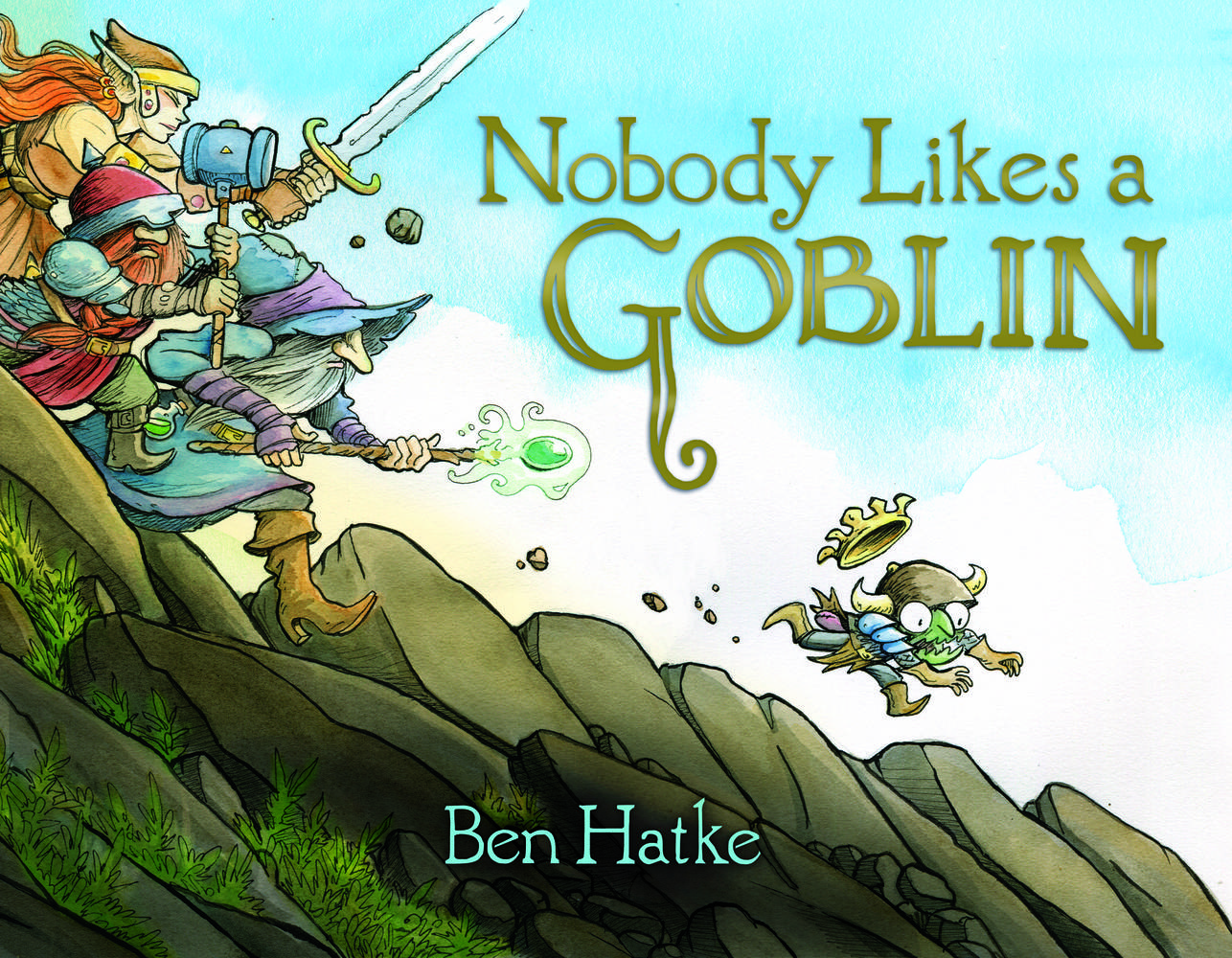

Hatke, Ben (2016) Nobody Likes a Goblin. New York: First Second.

Opening Lines: "Deep in a dungeon the bats were sleeping soundly, / and Goblin woke to a new day./ He lit the torches. He fed the rats. He gnawed an old boot for breakfast, and he thought about the day ahead."

In this picture book by Ben Hatke, (which seems to have been a character study for his recently released graphic novel Mighty Jack and the Goblin King) Goblin likes to pass his time with his friend Skeleton. Then a group of adventurers storm the dungeon and take everything, treasure, Goblin's furnishings, and even Skeleton. Goblin sets out to find his friend. Along the way he meets a hill troll who was raided by the adventurers who took his goose (which he calls his Honk-honk). Goblin tells the troll he will get the Honk-honk back. When Goblin enters human territory, he is met by fear, horror, anger, aggression, shouts of "Filthy Goblin!" and villagers carrying pitchforks and frying pans menacingly.

Goblin finds Skeleton and flees from the adventurers. He hides in a cave, feeling that nobody likes a goblin. Then he finds more goblins in the cave and they scare the adventurers away, taking their stuff (and some human friends) to start a new community. (The Troll gets his Honk-honk back.)

It struck me that though this is a fine picture book for kindergarten and first grade, it might also be useful for middle school or high school history classes. The way Hatke draws the adventurers, they are clearly what we could traditionally think of as protagonists, heroes, or good guys. In fantasy novels, such adventurers frequently defeat goblins, trolls, and other creatures and take treasure or whatever else they need from them. We accept this narrative as it is told to us -- assuming the treasure is ill-gotten gain and that the creatures are dangerous and somehow in the wrong. This story turns that around though, and presents the story from the perspective of the group that is usually thought of as the bad guys -- in much the same way that Howard Zinn's History of American Empire looks at history from the perspective of those who lost the battle, the war, or the negotiations.

I don't mean to suggest that Hitler's actions were justifiable, or that we need to understand that there are two sides to the Armenian or Rwandan genocides -- clearly within the sweep of history there are those who act from a morally reprehensible view of the world. At the same time, though, our students are taught to automatically accept their own history as being righteous and justifiable. This book may offer a way for students to reconsider those positions -- but it does so in a way that is disconnected from our world. Thus in-class conversations might be possible without the interference of deeply held and unquestioned contextualized political presuppositions.

The art work, as in everything else Ben Hatke does, is beautiful. Hatke illustrates things with enough detail to make settings and characters real enough that we can sympathize with them, yet also keeps the layouts simple enough that the reader can follow the story effortlessly. History teachers might think of having a look at this one.

No comments:

Post a Comment